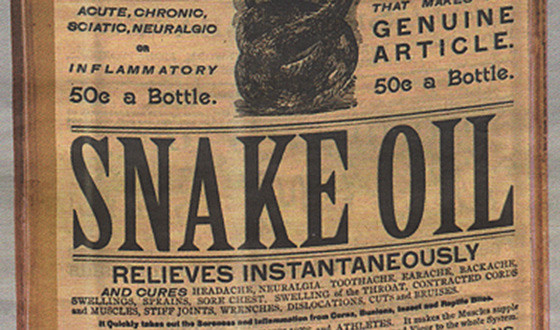

As a professor of management, I am grateful for the opportunity to equip managers (and aspirant managers) with the knowledge they need to develop and leverage their people, and few things bring me as much pleasure as when our students take insights discussed in class and apply these concepts to improve their organizations. However, I’ve also become increasingly disenfranchised by the pop psychology (i.e., snake oil) being sold to eager managers today under the guise of science. It’s one reason I co-founded a workforce analytics company to help managers better understand and leverage their human capital.

Among managers, there is arguably no more misunderstood concept than employee engagement.

Spurred on by the Gallup Organization and isomorphic pressure, most enterprise organizations (and even small businesses) deploy some form of engagement assessment to their employees. Top managers also take the summary results provided from these engagement surveys and even link their bonuses to overall workforce engagement.

In discussions with managers, I will often hear sentiments like the following:

“If we only had an engaged workforce, then our performance would really take off.”

“We are struggling to keep our Millennials engaged.”

“I’m proud that we link compensation to engagement. It shows that we care about our employees.”

Unfortunately, the evolution and application of this concept have occurred largely without understanding what engagement does (and doesn’t do) in your workforce.

To understand engagement, you have to go back to its roots in the job satisfaction literature, and specifically reference the work of Ed Locke (now Professor Emeritus at Maryland; best known for his contributions to goal setting theory). In 1969 and 1970, Locke published two papers that were incredibly important for understanding the operation of job satisfaction and its later counterpart, engagement. In these papers, Locke found evidence that employees feel more satisfied with work when they realize their professional and personal goals, arguing that performance is an instrumental cause of job satisfaction.

Although some individual-level evidence shows a recursive relationship between performance and job satisfaction, the firm-level evidence is pretty eye-opening. Specifically, Benjamin Schneider and his colleagues (2003 – Journal of Applied Psychology) investigated whether employee attitudes or firm performance came first in causal ordering. With the exception of the pay satisfaction to firm performance relationship, they found that firm performance predicted aggregate workforce attitudes – not the other way around.

This makes good sense from a theoretical standpoint. When the organization is doing well, it has slack resources to reduce managerial spans of control, employee workloads, reward/compensate employees more, and take on new projects intended for growth (the byproduct of which is promotion). Thus, it’s easier for people to realize their professional and personal goals at work when their employers are doing well. However, when the organization is suffering, layoffs and pay freezes make goal accomplishment much harder to come by. Thus, employee engagement suffers. The key takeaway of this research is that engagement is an outcome of your organization’s performance, not the cause. This runs contrary to the pop psychology rhetoric being pushed by many consultants today.

What then are we to do with engagement?

Does it mean that engagement isn’t important? Quite the contrary. Engagement is an important managerial tool. However, to understand the operation of engagement, it’s helpful to envision your company as a car. If workforce performance is the engine to your organization’s car, then workforce engagement is your RPM gauge, or tachometer. This gauge tells you how the engine is operating. When your engine is in the “red zone,” you risk long-term damage to the engine if you continue to operate at that level of intensity. Thus, the operator of the vehicle can make efforts to reduce RPMs and reduce the risk of damage to the engine. We also know that there are problems with the engine when we have applied the gas pedal but don’t see movement in RPMs. Finally, you can sometimes gain extra “horsepower” by increasing RPMs.

In the same manner, workforce engagement isn’t a prescription – it’s a symptom. Practitioners will push back and note, “engagement is related to so many outcomes in organizations.” True. But so is the tachometer, and we have to understand the distinctions between correlation and causality to better leverage engagement.

I also often find managers conflating engagement with motivation. Motivation describes the direction, intensity, and persistence with which individuals pursue objectives. It is one of three drivers of performance (the other two being ability and opportunity), and motivation is strongly linked to performance across a century of research. But it’s not the same thing as engagement.

Because managers often don’t know the difference between engagement and motivation, you’ll find these measures conflated in workforce assessments. However, we have to be honest about what we’re assessing if we expect to make evidence-based prescriptions based on the findings, and lumping constructs together only reduces our ability to draw evidence-based conclusions (even as it allows assessment companies to link their metrics with performance).

Given this information, how should we use engagement? I suggest using engagement as you would your blood pressure. Specifically, workforce engagement is primarily useful as a diagnostic tool. Assess it, drill down, baseline engagement, and look for changes in employee, supervisor, and unit engagement across time. Negative changes in engagement are a signal that managerial intervention is needed – something is broken that should be fixed. Conversely, positive changes (or high levels) can provide insights into best practices that can be explored by your managerial team and adopted elsewhere within your organization.

What you should avoid is making workforce engagement the goal.

An engaged workforce is a pleasant thing, in the same way that well-functioning engines are more enjoyable to drive that clunkers. However, if you’re going to solve workforce problems, you must first look at engagement as a symptom, and not the solution. If you want to drive performance, instead focus on motivation, ability, and expanded employee opportunities to leverage their capabilities.

Of course, this entire process assumes that you have access to individual engagement data. Sadly, most third-party assessment providers don’t give you access to individual, or roll-level, data, instead providing summary reports on the organization as a whole or its divisions. This is of little utility in helping sick organizations get better, and keeping healthy ones well.

How should you respond?

Start assessing your assessments to understand what you’re measuring. Demand individual engagement data from your providers, and hold them accountable. If they refuse, move on. The aggregate data they have is of little diagnostic utility to you anyhow. Once you have individual data, begin tracking employee, managerial, and unit-level engagement trends across time, linking it to behavioral and financial metrics, and using it diagnostically. And above all: be skeptical about “managerial snake oil.”